My article As PoK rises in revolt against Pakistan, China continues infra-building in Shaksgam Valley appeared in Firstpost

The new infrastructure could give a tremendous advantage to China in case of a new conflict with India in the region

Today, we are living in a world where everything can be seen from the sky, which often makes human intelligence (humint) irrelevant.

The latest case is a road illegally built by China in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir (PoK). While in the old days, it would have taken months or years to discover the road passing close to India’s Siachen Glacier, satellite imagery of the new road was splashed over the Indian and foreign media.

The road, located in the Shaksgam Valley, branches out from an extension of Highway G219 (also known as the Aksai Chin road) and “disappears into mountains at a place approximately 50 km north of India’s northernmost point, Indira Col in Siachen Glacier,” according to India Today.

The construction that passes through Aghil Pass (India’s frontier with Xinjiang before 1947), was first flagged on X (formerly Twitter) by ‘Nature Desai’, an observer of the Indo-Tibetan boundary.

Tom Hussain, a Pakistani journalist who writes for The South China Morning Post, gave the Chinese motivation: “Pakistan is looking to develop new overland border crossings with China that would potentially boost the allies’ military interoperability against Indian forces in Ladakh and the rest of Kashmir.”

The Hong Kong newspaper asserted that the Gilgit-Baltistan region, today under Pakistan’s control, had proposed a new transit and trade route linking Xinjiang to Kashmir “[which] will increase Beijing and Islamabad’s military interoperability against Indian forces in the region”.

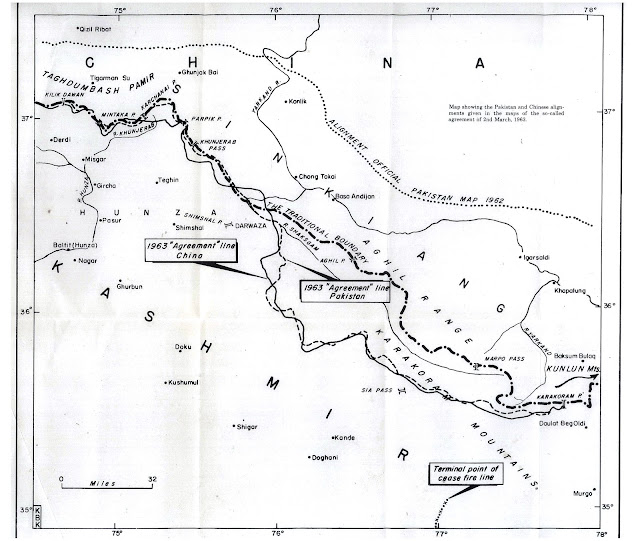

The spokesperson of the Indian Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) immediately asserted: “Shaksgam Valley is a part of the territory of India. We have never accepted the so-called China-Pakistan Boundary Agreement of 1963, through which Pakistan unlawfully attempted to cede the area to China. …We have registered our protest with the Chinese side against illegal attempts to alter facts on the ground. We further reserve the right to take necessary measures to safeguard our interests.”

It is, however, necessary to understand the history behind the Shaksgam Valley.

The Role of Western Powers

When China invaded northern India in October or November 1962, Delhi had no alternative but to ask for the help of Western nations, particularly the United States and Great Britain. At first, the United States seemed only too happy to offer support, thus gaining leverage over India, which until then had been ‘non-aligned’; this ‘neutrality’ often meant an alignment with Moscow, while Pakistan, a member of the SEATO and the Baghdad Pacts, always sided with the West.

When, at the end of November 1962, Washington realised that north India was in danger of being invaded by Chinese troops, it immediately declared its support for Delhi, but instead of helping India, London and Washington chose instead to try to settle the Kashmir dispute between their Pakistani ally and India.

On November 22, Averall Harriman, the American Under-Secretary of State, and Duncan Sandys, the British Commonwealth Secretary, visited the two capitals of the subcontinent to persuade the enemy brothers that it was time to bury the hatchet and find a solution to their fifteen-year-old dispute. Harriman and Sandys eventually signed a joint communiqué and asked the two countries to resume negotiations.

Although India, in an extremely weak position, had some doubts about the possibility of obtaining positive results from negotiations conducted in such particular circumstances, Nehru accepted.

On December 22, 1962, Nehru wrote to the Chief Ministers of the provinces: “I shall briefly refer to Indo-Pakistan problems, notably Kashmir. In another four days’ time, Sardar Swaran Singh will lead a delegation to Rawalpindi to discuss these problems. We realise that this is not a good time to have such a conference because the Pakistani press and leading politicians have vitiated the atmosphere with wild abuse and attacks on India. Nevertheless, we have agreed to go and to try our best to arrive at some reasonable settlement. It is clear, however, that we cannot agree to anything that is against our basic principles and ultimately injures the cause of Indo-Pakistan friendship.”

In the end, the two delegations held a series of six meetings, but nothing much came out of them. The first negotiations took place in Rawalpindi, where Swaran Singh and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the two foreign ministers, confined themselves to a historical presentation of the problem and a reiteration of their respective points of view.

Derailing Talks

But soon the negotiations went off on a tangent: the Pakistan government announced that it had reached an agreement in principle with China on its northern border problem (with Xinjiang). Hardly a month after the end of the Sino-Indian war, Pakistan was prepared to give China a piece of India’s territory (as per the August 1948 UN Resolutions).

Advertisement

What a slap in the face for India!

This agreement between China and Pakistan was obviously meant to derail the Kashmir talks.

It is indeed surprising that Pakistan, an ally of the United States and the Western world, should have chosen this moment to make the announcement. It was yet another proof that Pakistan expected nothing from the talks with Delhi, even though they had been initiated by their mentor, the US; at the same time, the support expected by India from the US for India’s northern borders had gone in smoke.

Nehru remained optimistic all the same, or perhaps, like the ostrich, preferred not to see anything. In a letter to the Chief Ministers, he remarked: “The talks have produced no results as far as our problems are concerned, except that they have reduced, to a small extent, the barriers of fear and mistrust that make it difficult to approach these problems.”

Negotiations continued, without tangible results, between 16 and 19 January in Delhi and 8 and 11 February in Karachi. Pakistan was only interested in a plebiscite for Kashmir, but India insisted on prior demilitarisation of the regions occupied by Pakistan.

The Treaty Discussed

On February 25, 1963, the government was asked in Parliament if the Note of Protest sent by Delhi to Pakistan regarding the Sino-Pakistan border treaty drew any response; if yes, what it said; and if the text of the agreement was available.

Dinesh Singh, the Deputy Minister in the MEA, answered: (a) No formal reply has been received to our protest note so far. (b) Does not arise. (c) No Sir.

At that time, Delhi did not even have a copy of the agreement.

Later, on the same day, Harish Chandra Mathur of the Congress asked again about the government’s reaction. Nehru answered: “The Government of India’s reaction is obviously unfavourable.” That was all.

The Treaty Cedes India’s Territory

China and Pakistan signed the agreement on March 2, 1963, by Bhutto and Chen Yi, the foreign ministers of the two countries. According to the two parties, this agreement was intended to promote “the development of good neighbourly relations and friendly relations and the safeguarding of peace in Asia and the world.”

In Article 1, it was acknowledged that the border had never been formally demarcated, and that the two countries wanted to draw it on the basis of “the traditional and customary border.”

As the Pakistani and Chinese maps did not match exactly, it was decided that the topographical features on the ground would be decisive.

It should be noted that in its description of the border, the agreement mentions the Karakoram Pass as the eastern end of the border. In practice, this seems to mean that the Siachen Glacier was occupied by Pakistan at the time. This was, of course, not the case. In fact, the Siachen glacier, long unexplored, has never been occupied by Pakistan, and it was only in 1984 that India took control of it.

Article 6

More interesting is Article 6, in which Pakistan and China agreed that after the settlement of the Kashmir dispute between Pakistan and India, “the sovereign authority concerned will reopen negotiations on the boundary with the Chinese Government so as to sign a formal boundary treaty to replace the present agreement.”

It means that even if the 1963 agreement was considered ‘legal’, which it is not, China is today building a road on a territory that is only temporarily with China. It is clearly a provocation in retaliation for India refusing to budge in Depsang and Demchok in Ladakh.

It remains that the new infrastructure could give a tremendous advantage to China in case of a new conflict with India in the region.

After maps of the new roads were published, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar reasserted that Pakistan-occupied Kashmir is part of India; he also mentioned the resolution of the Indian Parliament, which states that PoK is part of the country, and observed, “So, what will happen in the future? Very difficult to tell. But, I always tell people one thing, today PoK is in the consciousness once again of the people of India.”

In the meantime, the people of Gilgit-Baltistan have started revolting against the Pakistani state. The game is certainly not over.

Tail End: India will soon have the occasion to protest again; Pakistan and China plan to ‘realign’ the Karakoram Highway to avoid Attabad Lake, which is prone to landslides.