This article appeared under the title Changing the Demography of the Border in the Indian Defence Review (Vol 35.4) Oct-Dec 2020

Here is the link...

The Sixth Tibet Work Forum (TWF), held in Beijing on August 24 and 25, 2015 was a turning point for the Tibetan plateau.

Tibet Work Forums are large meetings called every 5 to 10 years to discuss the CCP’s Tibet policies. They are attended by all the members of the powerful Politburo's Standing Committee, members of the Central Committee, senior PLA generals, United Front Work Department officials and regional leaders.

Previous Forums were held in 1980, 1984, 1994, 2001 and January 2010, all in the Chinese capital. What is of interest to India is that the TWFs usually decide the fate of Tibet for the next five to ten years …as well the development on the border with India.

One of the main decisions of the Sixth gathering, presided over by President Xi Jinping, was to develop tourism as the main activity on the plateau; Tibet soon became a large entertainment park; a thousand times larger than Disneyland.

Beijing began marketing the Land of Snows as the ultimate ‘indigenous’ tourist spot for the Chinese to spend their holidays, this became Tibet’s USP (Unique Selling Proposition). It brought nearly forty million Han tourists to the plateau in 2019.

The Next Step: Further Hanisation of the Plateau

The Seventh TWF was held in Beijing on August 28 and 29.

While the previous TWF completely escaped the Indian (and the world) media, this one got wide coverage; the Seventh TWF was a crucial event not only as far it concerns the fate of the Roof of the World, but also for the presently tense Indian frontiers, as it took place at the time India faces a precarious situation in Ladakh.

It is necessary to study the TWF’s outcome, particularly because it defines the policies for China’s western border (this explains the presence of the entire Central Military Commission, as well as the service chiefs, including the Chief of the PLA Navy), at the Forum.

The Seventh TWF was given large publicity; the main TV report lasted more than 14 minutes, mostly quoting Xi Jinping and showing the large ‘masked’ gathering; a detailed report (in Communist jargon) was immediately issued. The select attendance shows Tibet's extreme significance for the Communist Party.

Incidentally, the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR) and Tibetan-inhabited areas of four provinces (Sichuan, Gansu, Qinghai and Yunnan) are now clubbed together as far as Beijing’s policies for the plateau are concerned.

The Timing of the Forum

The TWF was also held at a time Xi Jinping faces more and more reprobation and condemnation from around the world, following Beijing’s reckless moves on the Indian border and elsewhere.

It also came two months before the Fifth Plenum of the Communist Party of China, which has to take difficult decisions for the Middle Kingdom's economy; in 2020, Beijing is also celebrating the 70th anniversary of the so-called Liberation (read ‘invasion’) of Tibet, as well as the 55th anniversary of the creation of the Tibetan Autonomous Region (TAR), which has never really been autonomous.

To understand the TWF’s importance for India, it is necessary to remember Xi’s well-known theory that China “must adhere to the strategic thinking that to govern the nation, we must govern our borders; to govern our borders, we must first stabilise Tibet”. Since the month of May, we understand better why China wants to stabilize and control its borders with India.

The Sixth TWF resulted in poverty alleviation schemes which saw the construction of hundreds of ‘moderately-well-off’ villages (‘ghettos’ say the Tibetans), many of them close to the border with India.

Beijing’s untold rationale is that it is easier to control the ‘masses’ when they are sedentary and settled in well-connected villages (via Wifi and surveillance cameras); it is a fact that today the whereabouts and actions of the ‘resettled’ villagers can be controlled through their mobile phones and other surveillance gadgets.

Looking at the TV report of the TWF, one was struck by the fact that no monk attended the Forum. For a society which has traditionally been based on “the Harmonious Blend of Religion and Politics,” it is strange to say the least. Even Gyaltsen Norbu, the Chinese selected Panchen Lama, a favorite of the Chinese media, was nowhere to be seen. He is probably too young (and unsafe) for the Communist hierarchy.

It is not only the lamas who were missing in action. As far one could recognize the masked faces, hardly any Tibetans were present, even though all the speeches (and the TWF itself) are around the welfare of the ‘masses of all ethnic groups’ in Tibet (‘all ethnic groups in Tibet’ is an euphemism to hid the large migration of Hans on the plateau).

The Ten Musts

In his speech, Xi Jinping emphasized ‘The Ten Musts’ to “fully implement the Party's strategy of governing Tibet in the New Era;” he went through ten areas or ‘musts’. The objective, he observed, was to build a new socialist modern Tibet that is “united, prosperous, civilized, harmonious and beautiful.”

The CCP’s General Secretary pointed out: “Practice has fully proved that the Party Central Committee’s policies on Tibet work are completely correct, and that Tibet’s sustained, stable and rapid development is an important contribution to the overall work of the party and the country.”

He congratulated the comrades struggling on the ‘snowy plateau’, especially the cadres who serve on the frontline, i.e. the border with India.

Although Xi loves to speak about regional autonomy, it is clear that the Tibetans do not have much say in the matter. Why, for example, seventy years after the so-called ‘liberation’ of Tibet, has no ethnic Tibetan been made Party Secretary in Tibet? Has Tibetan ever made it to the Politburo? The reason is that the Han still do not trust the Tibetans.

Poverty Alleviation Scheme

An important way to ‘govern the borders’ is the development of model villages; this has serious implications for India’s defence, as the demography of the border will slowly be changed.

On December 24, 2019, China Daily announced that in 2019 in China, more than 10 million people were expected to be lifted from poverty; some 340 counties would no longer be labeled as 'impoverished'. This was stated by Liu Yongfu, director of the State Council Leading Group Office of Poverty Alleviation and Development in Beijing.

Liu particularly mentioned the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), as well as the four provinces where ethnic Tibetan people live (particularly in three prefectures of Gansu, Sichuan and Yunnan), the southern part of the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region is clubbed with these areas.

Liu’s report added: “In the renewed effort to combat poverty, local authorities were barred from merely handing out State benefits to farmers. Instead, they were required to adopt targeted measures in developing local industries and creating jobs that would help the poor attain sustainable incomes.”

This obviously raises the question, why have these areas, 'liberated' 70 years ago, remained so poor? The Communist Party has a lot to answer.

Ghettoization of Tibet

In October 2020, Xinhua announced that China had realized a historical feat: “Tibet eliminates absolute poverty”.

Wu Yingjie, Tibet’s Communist Party Chief, called the achievement a "major victory, as by the end of 2019, Tibet had lifted 628,000 people out of poverty and delisted 74 county-level areas from the poverty list …the average annual net income of poor people in Tibet had risen from 1,500 yuan (US$ 220) in 2015 to 9,300 yuan (US$ 1,400) in 2019.”

Wu added: “Since the beginning of this year, Tibet has shifted its focus from tackling absolute poverty to consolidating poverty alleviation achievements.” It was a major victory in poverty alleviation “attesting to the advantages of the socialist system,” he said.

A document released during Wu’s press briefing spoke of a major achievement for China's poverty alleviation campaign in the New Era: “Since 2016, Tibet has spent 74.8 billion yuan (US $ 11.25 billion) of agriculture-related fund in poverty alleviation, with an average annual increase of over 15 percent.”

Wu particularly cited relocation programs: “since 2016, a total of 39.89 billion yuan (US$ 11.25 billion) has been invested in over 2,900 poverty alleviation projects, which helped lift more than 238,000 impoverished people out of poverty and benefited more than 840,000 people.”

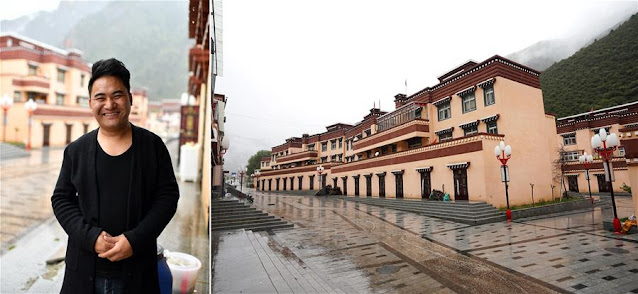

The main characteristic of the scheme is the ‘relocation’ of population in new ‘model’ villages known as ‘Xiaokang’ (‘moderately well-off’) villages, looking like ghettos where the populations can be better controlled and where Han colons can be brought in.

Wu affirmed: “Authorities in Tibet have made great efforts in relocating impoverished people living in severe natural conditions to areas with relatively rich production materials and better infrastructure.”

Nine Hundred Fifty Five Model Villages

The figures are mind-boggling; according to Wu: “To date, the construction of 965 relocation sites [villages] has been completed and 266,000 people have moved into new houses. The relocation programs were carried out entirely on a voluntary basis.” It is estimated that some 200 of these villages are located near the India border.

The fact that the ‘relocation’ has been voluntary is extremely difficult to believe; the pretext to transfer large populations, including nomads, is the issue of rarified oxygen on the plateau. This is a strange argument when one knows that the Tibetans have lived for centuries in these conditions and are hence well acclimatized; however, this does apply to the new Han colons ‘sharing’ these villages in what is called ‘ethnic mingling’.

The Chinese propaganda quoted one Thubten Khedrup, professor at the Tibet University in Lhasa saying that “a third-party assessment on the anti-poverty efforts in Tibet showed that the satisfaction rate among local people in the region was over 99 percent.”

In these circumstances, do the Tibetans have a choice, but to be happy?

Chinese TV daily shows videos of the new settlers arriving with forced smiles on their faces. They often travel by bus and trucks from remote places to be ‘happily’ resettled in a new environment.

Relocation of Population

On December 9, 2019, Tibet’s Poverty Alleviation Office published a notice saying that the last batch of 19 counties and county-level districts had finally shaken off poverty: “Tibet was a tough nut to crack in China’s poverty relief campaign due to its harsh natural conditions and complicated historical reasons. In 2015, the occurrence rate of poverty in Tibet was as high as 25.32%," commented a Chinese website.

The article takes the example of a Tibetan family who moved to a new house from Rongma Township in Nyima County of Nagchu Prefecture to Lhasa in 2018 (Nagchu is located at an altitude of more than 5,000 meters).

The website said that it was the first high-altitude exemplary site of ecological relocation in Tibet: “From June 10 to 18 in 2018, 571 herdsmen moved in two batches to Lhasa which is over 1,000 miles away.” This is just an example.

New Villages on the Border

More worrying for New Delhi are the relocations to Xiaokang villages located on India's borders.

On September 30, Xinhua noted that China had planned to invest 19.78 billion yuan (US$ 2.8 billion) in a relocation program to build 60,931 houses in around 970 settlements for 266,000 poverty-stricken citizens in the TAR.

It was said that by the end of August, 93.6 percent of the investment fund had been used and 56,000 houses had been completed: “Tibet seeks to lift 266,000 residents out of poverty by relocating them from harsh living conditions and ecologically fragile areas, of whom 3,359 from 939 families originally lived at an altitude of over 4,800 meters.”

Again according to Chinese news agency: “Tibet has been using relocation as a means of poverty reduction. By offering job opportunities in industrial parks and cities, the relocated residents are ensured ways to make a better living.” Though 'industrial parks and cities' are mentioned, the relocation is simply done in new villages, the industry may follow later.

Yume, Xi’s Model Village

How it started? Soon after the conclusion of the 19th Congress in October 2017, President Xi Jinping wrote a letter to two young Tibetan herders who had written to him introducing their village, Yume, north of Upper Subansiri district of Arunachal Pradesh.

Xinhua then reported that Xi “encouraged the herding family in Lhuntse County, near the Himalayas in southwest China's TAR, to set down roots in the border area, safeguard the Chinese territory and develop their hometown.”

Xi acknowledged “the family's efforts to safeguard the territory and thanked them for the loyalty and contributions they have made in the border area. Without the peace in the territory, there will be no peaceful lives for the millions of families.”

The two Tibetan girls, Choekar and Yangzom had told Xi about their “experiences in safeguarding the border area and the development of their township over the years.”

It appears that many Tibetans from the nearby villages now want to move their homes to Yume. Choekar's sudden celebrity will certainly help her village to grow exponentially ...and the border to be better protected. Against who, if not India!

Today, Han tourists have already started pouring into the village.

The same article affirms that Yume, located about 200 kilometers from the county seat of Lhuntse (which will soon have an airport), is a 'happy' village: "with the development of economy and the improvement of environment of Yume Township [yes, it has become a township!!], it has built numerous new houses for local villagers." But local Tibetan villagers are clearly not in majority anymore.

There is a definitive plan to repopulate the borders with India by creating new model 'townships'. This should be a serious worry for Delhi.

Since it was adopted by President Xi Jinping, Yume had become the Model Township for the 200 or so other 'Xiaokang' villages near the Indian border.

It probably means that China will have a new population of ‘migrants’ selected for their good behaviour on the Indian border.

It is still not clear if these ‘migrants’ are Tibetans or Hans; there is probably a blend; the scheme is called “The guardians of the sacred land and the builders of happy homes”.

Infrastructure and Xiaokang Villages: the Case of Metok

Metok means ‘Flower’ in the Tibetan language; till 2013, it was the last county in China without a road. It is located in Nyingchi City (Prefecture) on the lower reaches of the Yarlung Tsangpo River which becomes the Siang as it crosses the Indian border and then the Brahmaputra in Assam. A Chinese website said that Metok County “boasts of amazing natural landscapes due to its unique geographical position. Before the traffic opened, people could not reach Metok except by walking; getting in and out of Metok was a dangerous journey.”

It further adds: “The construction of roads to Metok is a tough task because of the complicated geological conditions and disastrous weather. With several attempts thwarted in the last decades, a 117-kilometer highway connecting Metok with neighboring Bomi County finally opened on October 31, 2013.”

In 2019, according to China Tibet News, the county has 46 administrative villages (including one so-called multi-ethnic inhabitation area consisting of Monpas, Lhopas, Tibetans and Hans) with a total population of 13,725.

In 2018, nearly 230,000 outsiders visited what used to be considered the last paradise on earth: “[it] created more than 160 million yuan (24 million US$) in tourism income. Nearly 9,000 acres of organic tea gardens directly provided income to nearly one-third of the total population.”

To get rich, first build the road was the motto of the Chinese Government and with the road, tourists come. And let us not forget that the infrastructure is for dual-use (civil and military).

Linking Infrastructure Development with Border Defence

Most of the times, the Xiaokang villages are linked to infrastructure development, particularly on India’s border; hundreds of examples could be given; to cite one, the Pai-Metok (Pai-Mo) Highway linking Nyingchi to Metok, north of Upper Siang district of Arunachal Pradesh will be opened in July 2021.

On October 12, 2020, it was reported that the Huaneng Linzhi Hydropower Project Office (ominously, a dam company) was building the road in most difficult terrain to effectively improve the current transportation facilities from Nyingchi and Metok, as well as the livelihood of the villages and towns along the route. The new Highway will be constructed with an investment of 2 billion yuan (0.3 billion US$): “The project will be fully completed by the end of September 2022. After the completion of the Highway, the length of the road from Nyingchi City to Metok County will be shortened from 346 kilometers to 180 kilometers, via Jingpai Town in Bomi County and the driving time will be shortened from 11 hours to 4.5 hours.”

The Highway starts in Pai Town in Milin County of Nyingchi and uses a long tunnel to pass through the Doshong-la Mountain, ending South of Metok town, close to the Indian border (Upper Siang district). The new highway will be 67 kilometers long. In strategic terms, it will be a game changer and greatly accelerate the developments of new model villages, and therefore relocation of populations.

Other Villages

These Xiaokang villages are located all along the Indian border from Rutok in Ngari Prefecture in the West to Rima (opposite Kibithu) in the Lohit valley in the East; a few model villages have been built on the Chinese side of Line of Actual Control (LAC) in Ladakh, other north of the McMahon Line in Tsona area.

China Tibet Online reported that on July 26, 2019, Gyalsten Norbu, the Chinese-selected Panchen Lama traveled to Jaggang Village in Rutok County of Ngari Province ‘for survey and research’; he paid a visit to two Tibetan families. The Chinese website explained, “it is a typical plateau village,” though it is not an ordinary village, it is also known as Chiakang and is situated very close to the border in Ladakh, just across the Kailash range. It seems that it is the first time that such a ‘senior’ religious leader, adventures forth himself on the Indian border, which China says is ‘disputed’.

A few kilometers away, on the Chinese side of Line of Actual Control (LAC) is another just-built ‘model’ town at Demchok.

Yet another village has recently received a lot of publicity, it is Jiru, located in Kampa Dzong (county), just north of the Sikkim border.

An article in The People's Daily: “The flower of national unity blooms on the border of the motherland.” It probably means that it will inhabited by Hans settlers; Jiru “in the southwestern frontier of the motherland, with an average elevation of 5,050 meters, at a distance of 5 kilometers from the China-India border, not far from seven passes [leading to India]. It is known as ‘the first village on the Sino-Indian border’,” says the Communist publication. There are 134 households with 538 people in the village: “In 2017, the village has been successfully transformed into a ethnic unity demonstration village.”

Strangely, no oxygen issue is mentioned in Jiru.

The People’s Daily added: “Although our village is located on the border, the consciousness of ethnic unity is deeply rooted in the hearts of the people. …Every year on the Army Day, the villagers will spontaneously visit the border guards and give them some mutton, potatoes and so on.”

Apart from Yume, Jiru or Metok, examples of Tsona (north of Tawang), Rima (north of Kibithu in the Lohit Valley), Tholing (in Western Tibet) often come in the news; to this should be added some more populated areas like Yatung in Chumbi Valley (near Sikkim) or Purang, close to the trijunction between Tibet, Nepal and India.

As the demography of these areas north of the Indian border is rapidly changing, Delhi should keep awake to these tremendous changes and develop its own border areas.

No comments:

Post a Comment